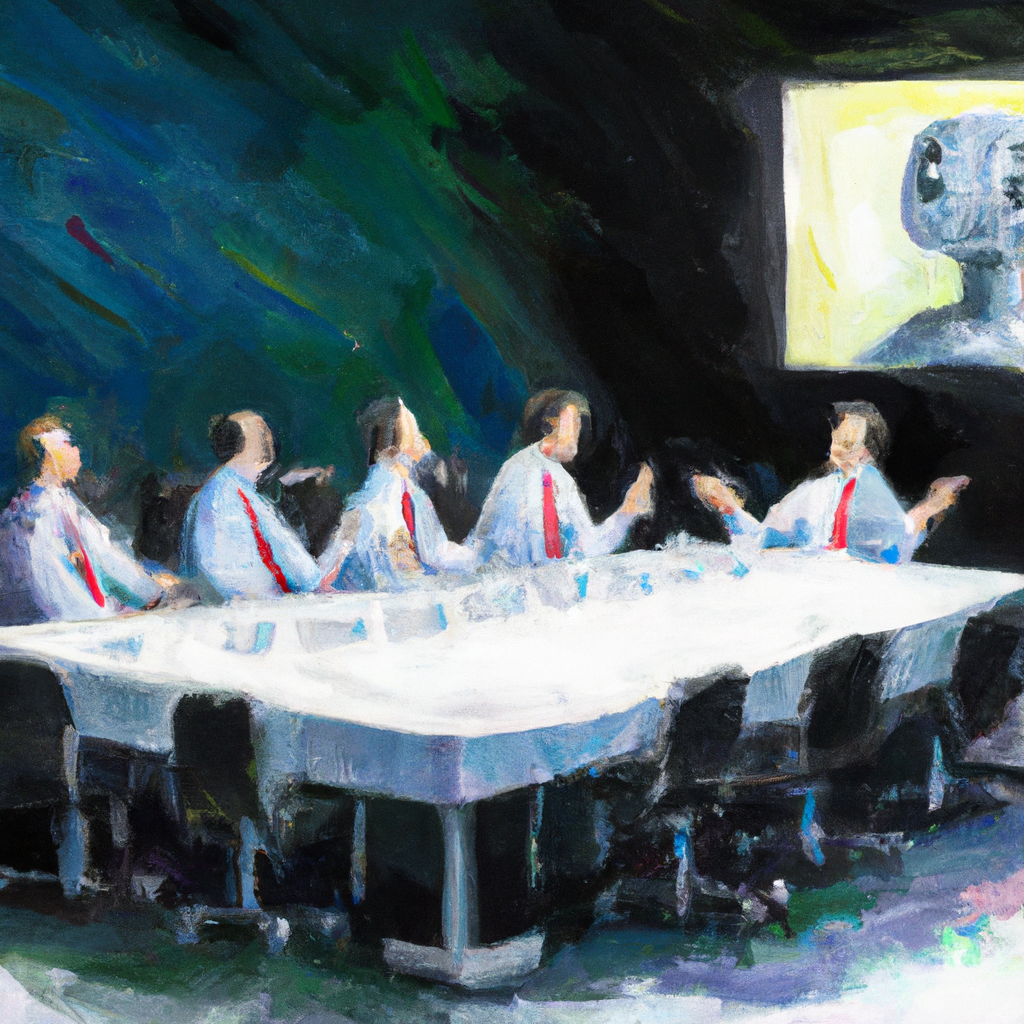

In an era dominated by materialism, Bernardo Kastrup’s insightful trilogy—”Why Materialism Is Baloney,” “Decoding Schopenhauer’s Metaphysics,” and “Decoding Jung’s Metaphysics”—offers a refreshing and profound exploration of consciousness and reality. Each book challenges conventional scientific perspectives, presenting a metaphysical idealism that places consciousness at the core of existence. This blog post delves into the essence of these books, providing summaries and practical habits to integrate their wisdom into daily life.

“Why Materialism Is Baloney: How True Skeptics Know There Is No Death and Fathom Answers to Life, the Universe, and Everything”

Summary

Kastrup critiques the materialist worldview that views reality as purely physical and consciousness as a byproduct of brain activity. He argues that this perspective is inadequate in explaining subjective experiences. Instead, he advocates for idealism, proposing the “filter hypothesis,” where the brain filters and localizes consciousness rather than generating it. This view aligns with Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious, suggesting that consciousness is fundamental and interconnected.

Practical Habits

- Mindfulness Meditation: Practice daily mindfulness to connect with broader consciousness beyond the ego.

- Reflective Journaling: Write about your experiences to gain self-awareness and understand your mind’s filtering processes.

- Engagement with Nature: Spend time in nature to reconnect with the broader flow of life and the interconnectedness of all things.

- Acts of Kindness and Compassion: Perform daily acts of kindness to foster empathy and a sense of unity with others.

- Limit Material Distractions: Simplify your life by focusing on experiences rather than material possessions.

“Decoding Schopenhauer’s Metaphysics: The Key to Understanding How It Solves the Hard Problem of Consciousness and the Paradoxes of Quantum Mechanics”

Summary

Exploring Schopenhauer’s division of the world into ‘will’ and ‘representation,’ Kastrup presents the ‘will’ as the intrinsic essence of everything and ‘representation’ as how the world appears to us. This idealist perspective suggests that reality’s fundamental nature is volitional and mental, addressing the paradoxes of quantum mechanics and the hard problem of consciousness. Schopenhauer’s framework offers a path to alleviate suffering by understanding and subjugating the will through meta-cognitive awareness.

Practical Habits

- Daily Reflection and Self-Examination: Reflect on your desires and impulses to understand their roots and motivations.

- Mindful Perception: Practice mindfulness by fully immersing yourself in sensory experiences.

- Meditative Contemplation: Engage in meditation to connect with the broader will and transcend immediate representations.

- Cultivate Intellectual and Artistic Pursuits: Stimulate abstract thinking and creativity to explore deeper aspects of existence.

- Acts of Selfless Service: Perform acts of kindness and service to others to transcend personal desires and align with the broader will.

“Decoding Jung’s Metaphysics: The Archetypal Semantics of an Experiential Universe”

Summary

Kastrup delves into Jung’s view of the unconscious as an active, creative force with its own will and language. Jung’s metaphysical idealism portrays life as a dream interpretable through the psyche’s symbolism. The psyche, comprising conscious and unconscious processes, is influenced by archetypes—primordial templates guiding our emotions, beliefs, and behaviors. Jung’s metaphysics suggests that the physical world and the collective unconscious are one, presenting a symbolic narrative that communicates the unconscious’s perspective to the ego-consciousness.

Practical Habits

- Active Imagination: Engage in daily dialogue with different aspects of your psyche through active imagination.

- Dream Journaling: Record and analyze your dreams, paying attention to recurring themes and symbols.

- Meditative Reflection: Dedicate time to meditative reflection, allowing unconscious content to surface.

- Creative Expression: Engage in creative activities to allow unconscious archetypes to manifest.

- Seek Synchronicity: Be mindful of meaningful coincidences, reflecting on their symbolic significance.

Conclusion

Bernardo Kastrup’s trilogy challenges us to rethink our understanding of consciousness and reality. By integrating the practical habits derived from these books, we can cultivate a deeper sense of meaning, alleviate suffering, and foster a more connected and fulfilled life. Embracing mindfulness, self-reflection, creative expression, and empathy can help align with this idealist perspective, promoting personal growth and a more profound understanding of reality.