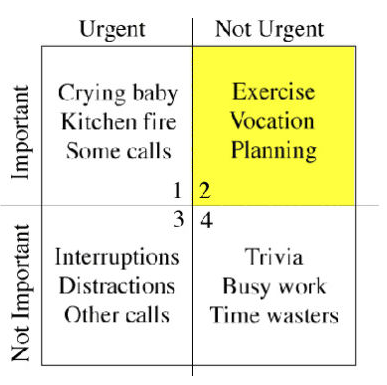

“What is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important.” – Dwight D. Eisenhower

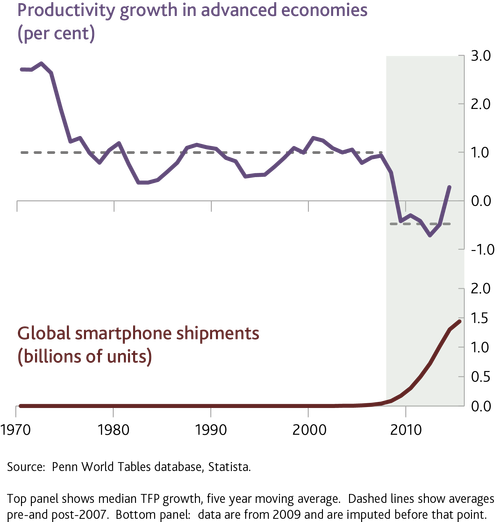

The productivity paradox states that even if we give workers new tools from the rapidly developing IT sector, their productivity slows down instead of speeding up. Some argue that we are way past this today, or that we are moving towards a split between GDP and gains in human welfare, but Dan Nixon at the Bank of England shows that 2007 (the year of the iPhone) was a major breaking point:

Of course, it is not the iPhone or any other smartphone that causes this decline. Rather, it is how we are using them: We check them about 150 times a day and not only to be productive. All kinds of social media and semi-interesting apps are causing big-time distractions, stealing time from the valuable work we can do. After each distraction, it can take us 20-25 minutes to regain our focus, just to be met by another distraction. As stated by Cal Newport in his book Deep Work, a “2012 McKinsey study found that the average knowledge worker now spends more than 60 percent of the workweek engaged in electronic communication and Internet searching, with close to 30 percent of a worker’s time dedicated to reading and answering e-mail alone.”

The answer to all this disturbance could very well be Deep Work, described by Cal as:

Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.

This should be viewed side-by-side with the opposite shallow work:

Non-cognitively demanding logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.

We can combine this with the Eisenhower matrix where two axels outline if things are Urgent/Not urgent and Important/Not important:

A problem we all meet is that being productive today often equals getting things done such as reaching inbox zero. This might feel great but can also fool us into believing such work is important per se. But given the enormous amount of ill-structured e-mails flying around, you might just have spent two hours in square 4 above while thinking you were in square 2. Yes, your inbox is empty, but you weren’t pushing your cognitive capabilities to their limits at all and you didn’t improve skills that are hard to replicate. Answering e-mails is very easy to do and is easy to replicate, but is it worth it compared to what you could have done instead?

A better start to the day might have been to quietly think through what is most important. And to do this while not being connected to e-mail, social media, or even other people. Cal Newport offers four rules to break our stressful and shattered work days:

- Work Deeply, meaning you shut off everything that can disturb you from performing your most valuable work.

- Embrace Boredom. Learn to put away the distractions and do nothing.

- Quit Social Media. Perhaps not completely, since it can be good for knowledge-building and more, but at least in periods.

- Drain the Shallows. Identify the areas that are most shallow in your life and cut those to a minimum.

To many, the above steps could be hard to put in practice and some might even say others shouldn’t dictate how to live one’s life, but here I agree with Cal:

A commitment to deep work is not a moral stance and it’s not a philosophical statement—it is instead a pragmatic recognition that the ability to concentrate is a skill that gets valuable things done.

This means that if you are interested in producing truly valuable work, you need to learn to switch off and tune out from the busy work. And the opposite is true: If you are not interested in being truly productive, then check your phone 200 times a day and keep thinking trivia, busy work and time wasters are important. Just don’t send those e-mails to the people who want to take valuable breaks to find out what is truly important.

Photo by Kristina Flour on Unsplash